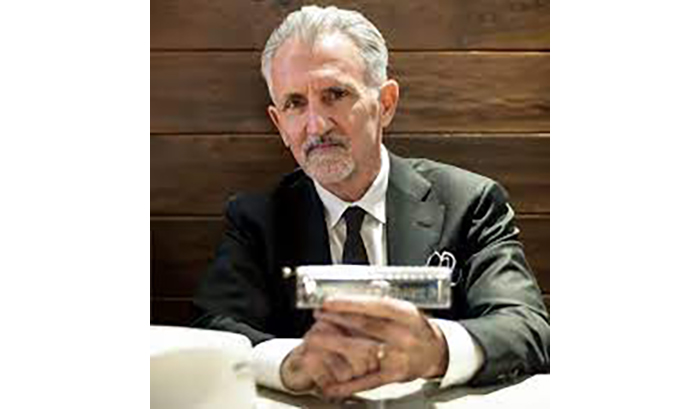

ICAHD UK Interview with George Bisharat, legal scholar, educator, commentator on the Middle East and blues musician

1 George, you are an American by birth so what is your connection to Palestine?

I was born in the United States to a Palestinian father and American mother. My father had come to the United States in 1946 to pursue a residency in eye surgery (prior to which he had opened an eye clinic in Gaza City), met my mother in Connecticut, her home state, married, and started a family. I was the fourth of five children.

2 While you were growing up, what part did Palestinian history and culture play in finding your identity?

Initially I had very little consciousness about our identity as such. However, what I did know was that I was part of a wonderful, loving family full of enchanting uncles and one aunt. They all doted on me and were truly marvellous people. So as I later became aware of our ethnic identity, it came with a very positive imprint. If these people (meaning my extended family) were Palestinians – then I was very lucky and proud to be one of them.

3 When did you first visit Palestine and did being there, witnessing the reality, influence your activism in raising the issue in the US?

My initial naivete about the political dimensions of Palestinian identity changed drastically after the 1967 war. Like many in the Arab American community, my parents both sprang into action as public speakers, writers, and organizers. This was also the era of the civil rights/Black power and anti-Vietnam war movements, so I was swept up in all of that, and was pretty engaged in political activism myself as an early teen and high school student. That continued when I started university and joined the Organization of Arab Students which, in those days, was the key organization for all political work related to the Middle East on US campuses. As a native speaker of English and US passport holder, I was thrust into a spokesperson role fairly early, and obviously had to study up to be competent at that. The next big step was when I attended the American University of Beirut as a junior-year-abroad student in 1973-74. That was, for me, a year of supercharged political education on Palestine and the region as a whole both in and outside of the classroom. It wasn’t until 1977, when I was in graduate school, that I visited Palestine for the first time. All that really did was confirm my strong conviction that Palestine was one of the most poorly understood examples of egregious injustice in the world – and it deepened my appreciation for the beauty and dignity of the Palestinian people.

4. Describe your education and the journey you have been on to gain high-level qualifications? Was advocating for Palestine what drove you?

From the very beginning of my undergraduate studies, I had been inspired by the examples of lawyers like Charles Garry in California, and others who had served progressive causes, and thus had targeted a career in law. Here in the US, of course, law is a post-graduate course of study, and one can study virtually anything as an undergraduate and still go on to be a lawyer. Therefore I studied what appealed to me most, which was anthropology. While politics were my greatest interest, I found political science to be very sterile and alienating, while anthropology provided a lens to examine political phenomena in a broader social and cultural context. Then I discovered legal anthropology by taking a course with Laura Nader at UC Berkeley. Laura is one of the most inspiring people I’ve ever met in any field, and through her I began to learn how to knit together my seemingly disparate interests in law, culture and politics, and Palestine by writing a paper on the legal dynamics of Israel’s expropriation of Palestinian lands. Laura encouraged me to present that paper at a professional conference; several years later it turned into one of my first professional publications in a US law review. But to answer your question directly: yes, absolutely, advocating for peace and justice in Palestine and elsewhere was what drove me through all of my studies.

5. Here in the UK when Israel bombed Gaza in 2014, there was a shift in popular option that resulted in significant growth in support for the Palestinian struggle. This happened again in May this year during Israel’s violent repression of Palestinians especially within East Jerusalem and in its bombardment of Gaza. How have these events influenced popular opinion amongst American citizens, including those with whom you interact?

There’s no doubt that a new generation of young people worldwide are growing up with an image of Israel that is very different than the one that prevailed as I grew up (I’m 66). In my youth, Israel was always depicted as the plucky little democratic “David” facing off against a horde of primitive Arab “Goliaths.” Never mind that none of that was ever true; it was an image that was successfully cultivated and propagated by establishment newspapers, film, and other media of popular culture. That façade is very difficult to maintain for those who have been raised on a steady diet of Israel pounding the obviously defenseless Palestinians of the Gaza Strip. However, Israel has suffered similar public relations setbacks in the past, going all the way back to its early history (the Lavon affair, the invasion of Suez, the bombing of the USS Liberty, the invasion of Lebanon, Sabra-Shatila, etc.), and has recovered from them. So while it would be nice to think that the tide of public opinion has permanently shifted, we must consider past experience and realize that change will not likely come so easily.

6 It has long been recognized that the UK is responsible for what has happened to the Palestinian population due to its signing of the Balfour Declaration which resulted in the Jewish Zionist movement transferring its population there and the establishment of the state of Israel. However, it is felt that it is the US that has enabled Israeli authorities to continue with its settler colonial agenda without being called to account. For the first time, members of the US Congress, currently amongst the Democratic party, are speaking up on behalf of Palestinians whether because of Israel’s arrest of Palestinian children, Israel’s disproportionate actions against Palestinian civilians or questioning US aid to Israel and military spending. Is this a phenomenon that will grow? Will it have any meaningful impact?

Let me first say that the UK did a whole lot more than just issue the Balfour Declaration. Its mandate over Palestine laid the material conditions for the establishment of Israel over the ruins of Palestinian society – deeds of much greater consequence than the mere words of the Balfour Declaration. But I do understand your point. Yes, I do believe that outspoken opposition to Israeli policies will increase within the Democratic party. That is in large part due to shifts in the base of the Democratic party, especially among its younger members, who are far more critical of Israel and sympathetic to justice for Palestinians than their elders. Nothing, however, should be taken for granted, and translating shifts in public opinion into policy change is not a direct or easy process. Our politicians are eminently capable of ignoring popular wisdom and preferences on many issues (such as gun control, for which there is overwhelming public support), not just Palestine, so it will require very focused effort to change incentives for US politicians so they actually respect the desires of their constituents.

7 You have been vocal in your call for one state to be established in all of historic Palestine. How did you come to this conclusion and what do you say to those, especially politicians and governments, who maintain their call for two-states?

I have always believed that in Israel/Palestine as elsewhere, justice breeds peace, while injustice breeds conflict. And it is perfectly obvious that a single state (which, in functional terms, is what we’ve had since 1967, when Israel became the de facto sovereign over all of former mandate Palestine) is the framework capable of realizing rights and justice for the greatest number of Jewish Israelis and Palestinian Arabs. How can nearly 2 million Palestinian citizens of Israel ever achieve equal rights in a Jewish state? How can the rights of individual Palestinian refugees to return to their native villages and homes in Israel be vindicated by immigration to the West Bank and Gaza Strip, which lack the space and/or resources to absorb them? While I support a single democratic state as a matter of principle, I would also observe that Israel has, by its relentless settlement of the West Bank, destroyed any possibility of establishing a genuinely sovereign Palestinian state. Continuing to call for two states when it simply cannot be achieved is tantamount to support for the status quo, which means continuing colonial advancement by Israel, and further displacement of Palestinians in favor of an apartheid regime of Jewish supremacy (to use B’Tselem’s term).

8. What is your response to those people who state that they don’t care if it is one state, two states, or five states as long as Palestinians have human rights? This also brings up the efficacy of international law. Is it useful for the struggle or does it just deflect from the need for political processes? In what way can IHL be integrated into, or harnessed to support, the struggle for Palestinian rights?

I’m sympathetic to the argument that states and sovereignty should be viewed as means to an end (achieving rights) rather than as ends in themselves. In that sense, the number of states is immaterial as long as each of them enables the fulfilment of the equal rights of its citizens. But that is not the aim of the currently prevailing two-state vision. Indeed, that vision is explicitly for the purpose of preserving Jewish privilege in a Jewish state, just in a smaller space than the current functional single state reality. Law, whether international domestic, can be an adjunct to a political movement for justice, but never in itself and probably never as a central feature of that movement. Law is more often an instrument of power and control; it can become an instrument of liberation when it rides on the shoulders of mass movements. The phrase I use is: law is the language in which political power expresses its victories. There are no short cuts to power. It has to be won through hard work and persistent struggle.

9. In recent years you have developed a new career as a blues musician known as Big Harp George. Are you abandoning your legal career for this new direction and why?

I have retired from full time teaching but not writing, research and public speaking. I have particularly lively intellectual ties to a community of scholars in Brazil, where I’ve been privileged to visit frequently over the last decade or so. I expect to maintain those connections. I started singing in bands even as a pre-teen, picked up harmonica in my early teens, and have played ever since, and seriously considered pursuing music professionally in my twenties. By that time, however, I was deeply immersed in my studies and work on Palestine, and that left little room for music, other than individual practice. But I have always viewed blues – my genre – as a medium of resistance and identified with its affirmation of life spirit against oppression and hardship. So investing more of my time and focus in music at this point in my life just feels like a shift of methods, to convey the same messages that I always have throughout my life.

10. What is the final message that you would like to leave with internationals who campaign for a just and sustainable solution in Palestine/Israel?

I recently stated to my daughter that I was beginning to believe that I might see a free Palestine within my lifetime. Perhaps I suffer from an excess of optimism. But the fact is that I feel more hopeful now than I have in a long time, mainly because of the wisdom, commitment, and energy that I am seeing in the rising generation in Palestine, here in the US, and elsewhere. This great challenge of achieving justice in Israel/Palestine will not be easy – it will require tremendous dedication and energy. We cannot achieve it without offering and receiving solidarity from others facing similar or parallel injustices. But it can be achieved. Let’s go out and make it happen, together.

Palestinian Lawyers and Israeli Rule: Law and Disorder in the West Bank by George Bisharat was published by the University of Texas Press and explores what it’s like for attorneys in Palestine to work under the conditions of a military occupation.

Watch George Bisharat’s blues performance of Alternative Facts.